Article by Jack Quail and Matthew Cranston, courtesy of The Australian

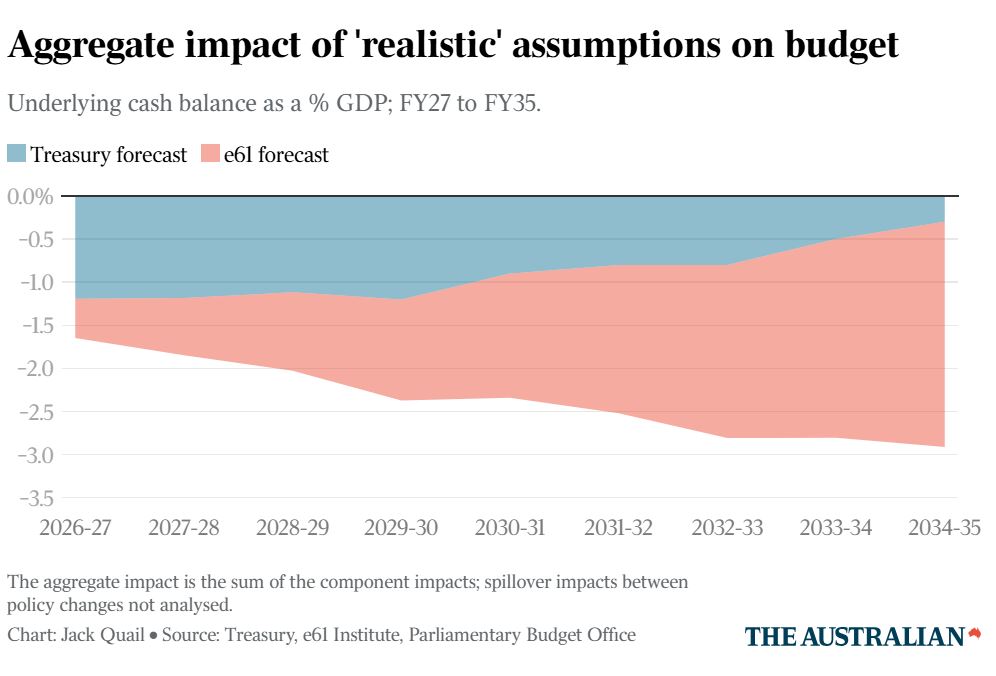

Treasury’s forecast that the budget will return to surplus in a decade is based on “fanciful” assumptions that if made even slightly more realistic would show Australia’s deficit swelling to almost $100bn within 10 years.

The budget papers on Tuesday projected a deficit every year until 2035-36 premised on expectations that productivity growth would return to its pre-pandemic levels, government spending did not increase further, and no bracket creep was returned to taxpayers.

Analysis by Lachlan Vass and Aaron Wong, researchers at the e61 Institute, an independent think tank, has dismissed those heroic assumptions, replacing them with more realistic parameters to demonstrate the true pressures on the budget, which is deep in a structural deficit.

The two have warned of a “significant worsening” in the budget bottom line, which could push to -2.9 per cent of GDP in 2035 and amount to a $100bn deficit in today’s dollars. That would far exceed the projected deficit for this financial year at $27.6bn or -1 per cent of GDP.

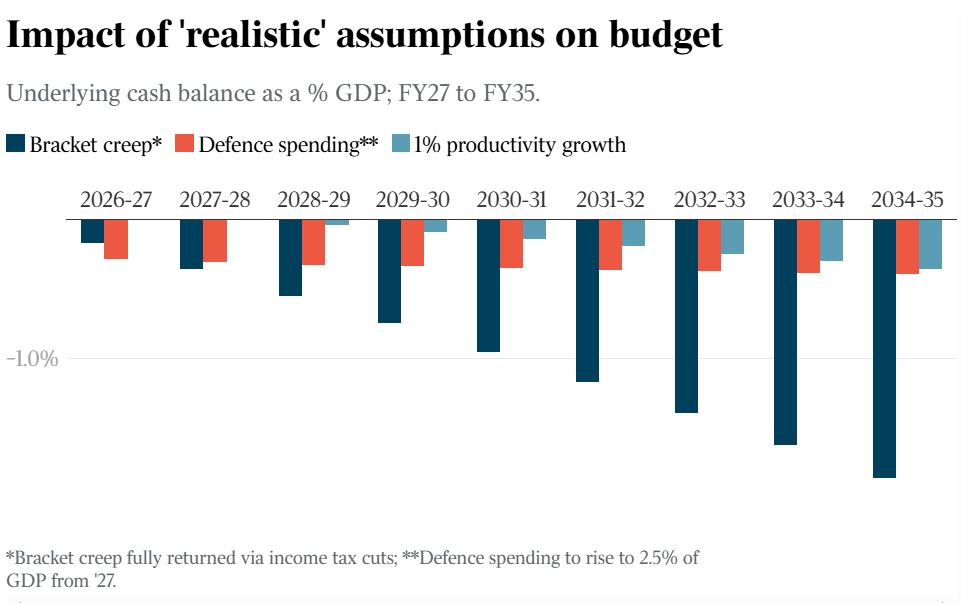

In reaching the realistic projection, the research altered the budget’s assumption that there will be no income tax cuts over the coming decade and rely on revenue from bracket creep which occurs when inflation pushes workers into higher tax brackets.

Both major parties, however, have routinely offered income tax cuts to address bracket creep, with the research assessing it is “extremely unlikely” there will be no cuts over the coming decade.

If governments were to fully return bracket creep via income tax cuts, the modelling estimated that the budget deficit could reach -1.9 per cent of GDP by 2035. Returning even the majority of bracket creep would still have “significant consequences” for the budget, the research noted.

Secondly, the modelling altered the budget’s projections for defence spending, which at its current level of $56bn accounts for approximately 2 per cent of the economy.

But amid heightened geopolitical tensions and pressure from the Trump administration for its allies to increase military expenditure, both major parties have foreshadowed a planned increase to defence spending.

Labor has committed to a target of 2.33 per cent of GDP by 2033-34, while there is widespread speculation the Coalition could push to 2.5 per cent.

Such an increase would have significant ramifications for the budget bottom line, the modelling showed. An increase to 2.5 per cent of GDP from 2027 and beyond would cause the budget deficit to more than double in size in 2035.

Finally, the research also took aim at the budget’s productivity growth assumptions at 1.2 per cent, which far exceed their current levels, warning that continued weak levels of productivity threaten to drag the nation’s finances deeper into the red.

By using a slightly lower, albeit still ambitious productivity growth assumption of 1 per cent, the pair estimated the budget deficit will significantly worsen by -0.4 per cent of GDP in 2035.

The new modelling came as the Productivity Commission issued a warning on Friday about Australia’s productivity levels that further undermine the Treasurer’s optimistic assumptions.

Labour productivity slipped 0.1 per cent in the December quarter and was down 1.2 per cent annually from a flat reading in the previous quarter.

“The data makes it clear that our productivity problem is not a flash in the pan – this is a long-term, structural challenge that requires dedicated attention from government and industry,” the commission’s deputy chair, Alex Robson said.

A new report from the commission noted that if such a rapid decline in productivity were to persist, there would be “serious consequences” for “all Australians”.

“The real problem with labour productivity is that we don’t seem to have improved labour productivity in over 10 years. And this should be the focus for policymakers,” it said.

It picked out the National Disability Insurance Agency and the childcare sector as potential drags on labour productivity.

Healthcare and social assistance labour productivity declined 0.4 per cent in the quarter and is down 1.2 per cent over the year.

“While a deliberate policy choice to underwrite social services in Australia, these sectors typically have below-average labour productivity so as they grow, average labour productivity falls.”

On a positive note, the commission said the growth in Australia’s younger workforce should improve in quality as workers gain experience in their new jobs.

“This may even suggest some potential upside for the productivity outlook,” the commission said.